Illustration:

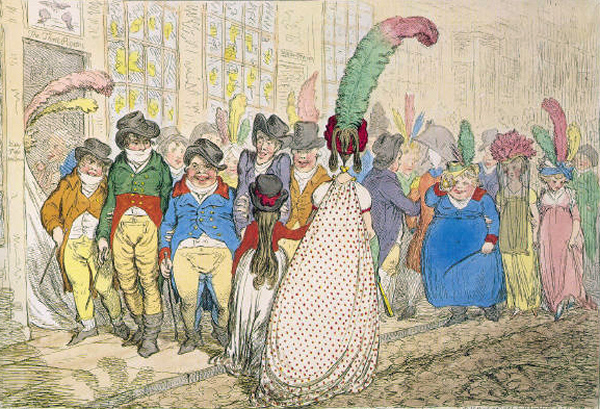

1. High-change in Bond Street, - ou- la Politesse du Grande Monde by James Gillray. Published by H. Humphrey of London, March 27th 1796.

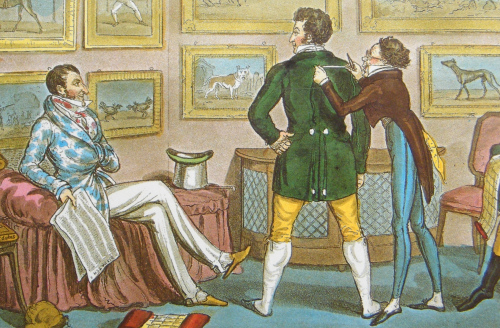

2. Jerry in training for a 'Swell'. Published as illustration in Pierce Egan's 'Life in London; or, The day and night scenes of Jerry Hawthorn, esq., and his elegant friend Corinthian Tom, accompanied by Bob Logic, the Oxonian, in their rambles and sprees through the metropolis... , illustrated by George and Robert Cruikshank. Published in London by Sherwood, Neely, and Jones, 1821.

3. Fashion plate, possibly from Le Petit Courrier des Dames, combining two prints previously published in Costume Parisien. Left: 'Redingot de Matin, pantalon a la Russe,' first published as Plate 1619, 1817. Right: 'Costume de Bal,' first published as Plate 1627, 1817.

4. Highland Folk Museum, Newtonmore, Scotland. Photo reproduced by kind permission by Laura Edwards.

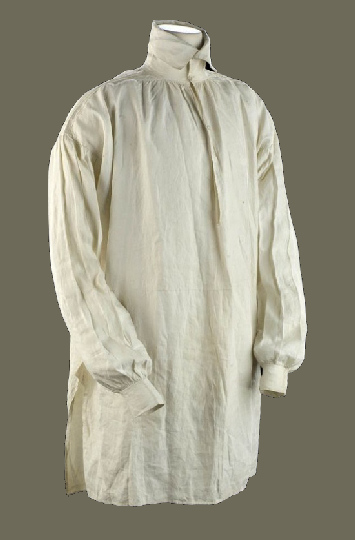

5. 1807 men's linen shirt, now in The National Maritime Museum

6. Detail caricature "The Dandies Coat of Arms" by G. Cruikshank. Published by Thomas. Tegg March 28, 1819

Notes on the text:

Unless otherwise stated, the source of most of this page is 'Savile Row' by Richard Walker (Kennedy), first published 1988 by Multimedia Books Limited, London; this edition published 1989 by Rizzoli.

a: Advertisement The Times, of Saturday 27 January 1800

b: The Eo-Nauts, of the Spirit of Delusion: A Serio, Comico, Logical, Eulogical, Lyrical, Satirical Poem, with Notes, Geographical and Critical, of Various Commentators, Lemuel Gulliver editor. Published by Chapple, 1813 p. 29

c: For example, today's Gieves & Hawkes have their roots in the Georgian era as Thomas Hawkes opened his tailor shop in 1771 and went on to dress both George III and his son George VI (The Prince Regent), getting his royal warrant in 1809. From 1793 onward the premises were at No.17 (later renumbered No.14) Piccadilly. James Gieve, however, starts his career under Meredith in Portsmoth, who is the one tailoring Admiral Nelson's uniform.

d: As an example of Regency male fashion see illustration #3 on this page.

e: "5547. Bath coating and duffel are light cloths, with a long nap like a double-raised baize used as winter's dress, for great coats, &c. It is of various colours; also white for women's petticats. Widths 4/4, 7/4, 8/4." - An Encyclopædia of Domestic Economy By Thomas Webster & Mrs. William Parkes. Published by Harper & Brothers, 1855 p 945.

f: Gronow Reminiscences

g: "The great Mr. Stultz, tailor, in Clifford street, who retired to France a few years ago, and was created Baron Stultz, died on the 17th of November, at his estate called Aires, in the South of France, after an illness of nine days. This estate cost him upwards of 100,000£. (we believe 103,000£.) He had another large estate near Baden on the Rhine.— About a year ago the Baron sent the Emperor of| Austria a present of 40,000£. to do with what he pleased, for which present he receive in return the Order of Maria Theresa, and the patent as Count Gothemburg. The Baron had great wealth in the bank at Vienna (Rothehild's.) His property, besides htse estates, exceeded 400,000£." —[Globe.] Quoted in American Railroad Journal and Advocate of Internal Improvements, February 2, 1833, p. 77.

h: List of London master tailors, 1799

i: "Brummell, though not possessing the patronage of a secretary of state, had the power of making men’s fortunes. His principal tailors were Schweitzer and Davidson of Cork street, Weston, and Meyer of Conduit street. Those names have since disappeared, but their memory is dear to dandyism; and many a superannuated man of elegance will give 'the passing tribute of a sigh' to the incomparable neatness of their 'fit,' and the unrivaled taste of their scissors. Schweitzer and Meyer worked for the Prince, and the latter was in some degree a royal favourite, and one of the household. He was a man of genius at his needle; an inventor, who even occasionally disputed the palm of originality with Brummell himself. The point is not yet settled to whom was due the happy conception of the trouser opening at the ankle and closed by buttons. Brummell laid his claim openly, at least to its improvement; while Meyer, admitting the elegance given to it by the tact of Brummell, persisted in asserting his right to the invention. Yet if, as was said of gunpowder and printing, the true inventor is the man who first brings the discovery into renown, the honour is here Brummell’s, for he was the first who established the trouser in the Bond street world." - Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 55, No. 344, June, 1844.

j: See under heading 'Jonathan Meyer, Beau Brummel and revolutionising the trouser' on the Meyer and Mortimer website

k: Letter of April 20, 1829, reprinted in Shops and shopping 1800-1914, p. 53.

l: A Journeyman Tailor. Poland Street, Oxford Street. – Notes to the People, by Ernest Jones, 1851, p 991-2

m: Unless otherwise stated information regarding underwear taken from The History of Underclothes by C. Willett and Phillis Cunninngton, the Dover 1992 slightly corrected version, first printed 1951 by Michael Joseph Ltd. London.

n: Old Bailey t18000709-52

o: Old Bailey t18000528-31

p: Old Bailey t18030914-66

q: See for example Old Bailey case t18010520-12, t18030914-66, t18130602-126, t18261026-149

r: Journal published by Richardson, 1821-1823.

s: Neckcloths, p 333, The Literary Speculum – Original essays, criticism, poetry No 5, March 1822.

Civet is a common source for musk perfume.

t: Data from The Wynne Diaries III, citation in The History of Underclothes, p. 102

u: More mornings at Bow Street: 1827, LIST of Necessarier to be provided by Stoppage 1799, Treatise on military finance 1809

|