|

Illustrations:

1. From Ackermann's Repository of arts, literature, commerce, manufactures, fashions and politics (1809) 'Harding, Howell, & Co.s grand Fashionable Magazine, No. 89, Pall Mall' (Plate 12: Vol. 1, No. 3, March 1809)

2. 'Cheapside', published 1813 in Ackermann's Repository of Arts Vol 9, Plate: 44.

3. Trading card, Waithman & Sons. Shawl and Linen Warehouse c. 1810

4. 'Linendraper', print from 'A Book of English Trades' by Richard Phillips, 1818 edition.

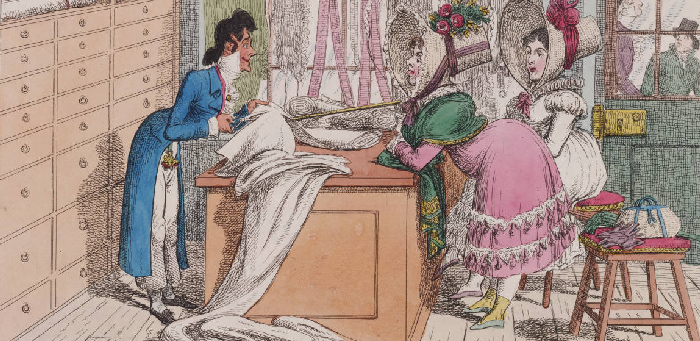

5.'The Habedasher Dandy' by Thomas Tegg, 1818. Printed by C. Williams

6. Dress shop 1777

7. 'The Ladies Dress Maker', print from 'A Book of English Trades' by Richard Phillips, 1818 edition.

8. Le Bon Genre, French caricature print from around 1815

____________________________________________________________________

Notes on the text:

For the information on this page I have made extensive use of M. Corina, 'Fine Silks & Oak Counters', published by Hurchingson Behman 1978. References to this source are marked "MC". For other sources see footnotes below.

a: See also Cotton Times: Understanding the industrial revolution

b: Existed in it's present form until 1820 when the partnership ended and Howell, taking most of their customers with him, established a new company as Howell & James, which lasted until 1900 when it was acquired by Debenhams. MC

c: Description of plate above: see the Shopping Mall page.

d: Jane Austen 'Pride & Prejudice' first published 1813, available as e-text

e: Trading card before 1813) Text: 'G. Sutton. Silk Manufacturer 53 Leicester Square, Wholesale & Retail. Handkerchiefs Figured, Fancy Main Color'd & Black. Sarsnet, Satins, Persians, Modes. Velvets, Bombazines, Barcelona Hkfs. Florentines, Mantuas and Armozines.' Also advertisement in La Belle Assemblee 1812 as G Sutton and 1813 as Sutton and Meeks.

f: Trading card c. 1810 Text: Waithman & Sons. Shawl and Linen Warehouse

g: Trading card 1813 Text: Cavendish House; Clark & Debenham; On the same termas as FLINT &.

Every Article of the best Quality FOR READY MONEY ONLY

Silk - Merchers, Haberdashers Hosiers, Milliners & Lacemen

No 44 Wigmore. Cavendish Square

FAMILY MOURNING

A large elegant assortment of Cottage Twills, Stuffs, Bombazines, Sarsnet, Satins Millinery -Pelisses and Dresses

h: Handbill after 1837. Text: Cavendish House; Promenade, Cheltenham:

No. 44 WIGMORE STREET, LONDON, and HARROGATE, YORKSHIRE

DEBENHAM, POOLEY & SMITH

beg to announce their intention of OPENING their NEW and EXTENSIVE PREMISES on MONDAY NEXT, when they will offer for Sale a Stock unrivalled in extent, and selected with the greatest care from the British and Foreign Markets, consisting of every novelty in

SILK, CACHMERES, SHAWLES, MANTELS, CLOAKS, LACE and EMBROIDERY; HOSIERY, FLANNELS and BLANKETS; MOREEN, DAMASK and CHINTZ FURNITURE; SHEETINGS, DAMASK TABLECLOTHES, and Line Drapery of every description; COBOURG and ORLEANS CLOTHS; A Large Lot of French Merinos, Exceedingky Cheao; READY-MADE LINEN, for Ladies and Gentlemen; Baby Linen and Children's Dresses of every kind; also

A CHOICE OF FURS

FAMILY MOURNING

FUNERALS conducted in the most careful manner, at moderate charges

i: The first possible patent connected to mechanical sewing was a 1755 British patent issued to German, Charles Weisenthal. Weisenthal was issued a patent for a needle that was designed for a machine, however, the patent did not describe the rest of the machine if one existed.

The English inventor and cabinet maker, Thomas Saint was issued the first patent for a complete machine for sewing in 1790. It is not known if Saint actually built a working prototype of his invention. The patent describes an awl that punched a hole in leather and passed a needle through the hole. A later reproduction of Saint's invention based on his patent drawings did not work.

In 1810, German, Balthasar Krems invented an automatic machine for sewing caps. Krems did not patent his invention and it never functioned well.

Austrian tailor, Josef Madersperger made several attempts at inventing a machine for sewing and was issued a patent in 1814. All of his attempts were considered unsuccessful.

In 1804, a French patent was granted to Thomas Stone and James Henderson for "a machine that emulated hand sewing." That same year a patent was granted to Scott John Duncan for an "embroidery machine with multiple needles." Both inventions failed and were soon forgotten by the public.

In 1818, the first American sewing machine was invented by John Adams Doge and John Knowles. Their machine failed to sew any useful amount of fabric before malfunctioning.

The first functional sewing machine was invented by the French tailor, Barthelemy Thimonnier, in 1830. Thimonnier's machine used only one thread and a hooked needle that made the same chain stitch used with embroidery. The inventor was almost killed by an enraged group of French tailors who burnt down his garment factory because they feared unemployment as a result of his new invention.

In 1834, Walter Hunt built America's first (somewhat) successful sewing machine. He later lost interest in patenting because he believed his invention would cause unemployment. (Hunt's machine could only sew straight steams.) Hunt never patented and in 1846, the first American patent was issued to Elias Howe for "a process that used thread from two different sources." Howe's machine had a needle with an eye at the point. The needle was pushed through the cloth and created a loop on the other side; a shuttle on a track then slipped the second thread through the loop, creating what is called the lockstitch. However, Elias Howe later encountered problems defending his patent and marketing his invention.

For the next nine years Elias Howe struggled, first to enlist interest in his machine, then to protect his patent from imitators. His lockstitch mechanism was adopted by others who were developing innovations of their own. Isaac Singer invented the up-and-down motion mechanism, and Allen Wilson developed a rotary hook shuttle.

Sewing machines did not go into mass production until the 1850's, when Isaac Singer built the first commercially successful machine. Singer built the first sewing machine where the needle moved up and down rather than the side-to-side and the needle was powered by a foot treadle. Previous machines were all hand-cranked. However, Isaac Singer's machine used the same lockstitch that Howe had patented. Elias Howe sued Isaac Singer for patent infringement and won in 1854.

j: House of Commons, Reports from Commissioners: Children's Employment, Trade and Manufactures, Sessional Papers XIV (1843) 555.

k: 'Socioeconomic Incentives to Teach in New York and North Carolina: Toward a More Complex Model of Teacher Labor Markets, 1800–1850' by Kim Tolley and Nancy Beadie. See also Alice Kessler-Harris, 'Out to Work: A History of Wage-Earning Women in the United States', published by Oxford University Press, USA. |